The World and Language Must be Interpreted

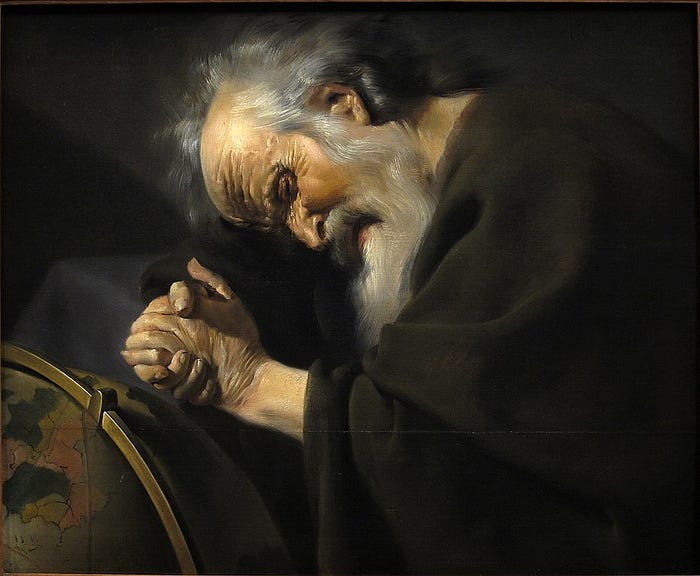

An Introduction to Heraclitus’ Philosophy of Language

Do you know where the word ‘philosophy’ comes from?

The first known use of the word in a way we know it today was by Heraclitus (c. 500 BC) when he said,

“those who are lovers of wisdom (philosophos) must be inquirers into many things” (DK22B35)

Thus, Heraclitus and others (e.g. Parmenides, Thales, and Anaxima…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to It's All Philosophy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.