Which of our senses do we use for philosophy?

Eastern philosophical traditions are often seen as not being critical or rational investigations of reality. Instead, they are considered to be mystical, tradition-focused, or just practical.

This characterization has been used by scholars to dismiss the work of intellectuals from countries such as India, China, Korea, and Japan, among many others.

Some even go as far as to not use the word “philosophy” to describe work from Eastern countries.

While such characterizations are not entirely without merit, Eastern philosophical traditions have a deep strain of critical and rational investigation within them.

In this essay, I will argue that some of the confusion about the nature of Eastern philosophy might rest on different ways of relating to thought in Eastern and Western Philosophy.

Simply put:

Western philosophical traditions’ focus on philosophy as seeing.

Eastern philosophical traditions’ focus on philosophy as listening.

I will do this by first looking at the early history of Indian philosophy. I will then show the influence of this listening model of philosophy in Kūkai, a Japanese Buddhist philosopher from the 9th century. I will conclude with some advantages a listening model has over a seeing model of philosophical investigation.

The Oral Tradition of Early Indian Philosophy

Eastern philosophical traditions see the goal of a critical and rational investigation into reality as having a better understanding of reality.

In classical Indian philosophy, understanding is a precise concept, meaning the use of reason in combination with experience.

In other words, in being rational, Eastern traditions see the use of reason alone as a mistake. Experience of things such as the world, people, customs, and traditions contribute to the mechanism of reason being fully complete.

The question is then how is one to carry out a critical and rational investigation which results in understanding as defined above.

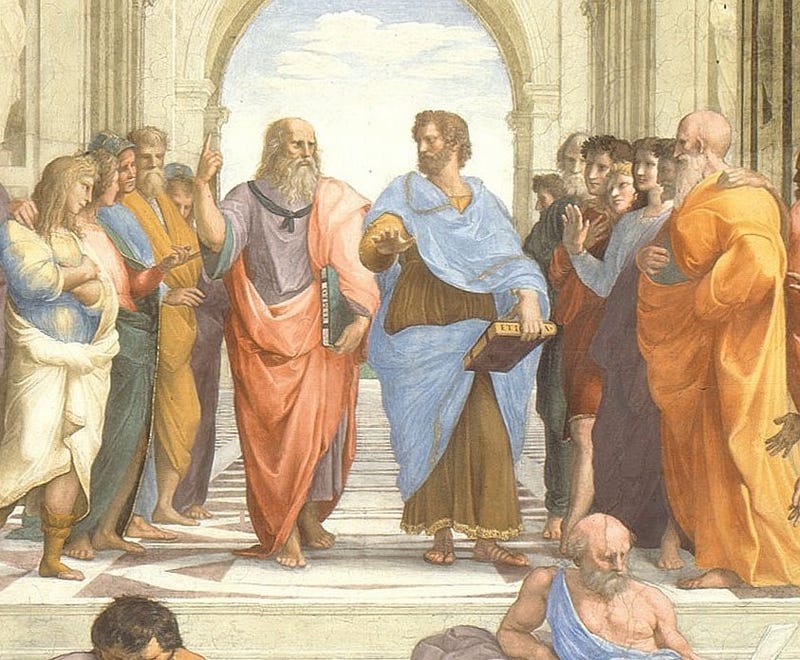

The Greek model was to look at the world.

For example, Plato uses the allegory of the cave to illustrate the process of coming to have understanding. What changes at each step in the movement to understanding is what one sees (e.g. shadows, things), with the highest form being what makes it possible to see (i.e. the sun, representing the good).

However, Eastern traditions focus on dialogue; using them as a means to work out what is seen.

It is in the stories and dialogues captured in the Vedas and Upanishads where understanding is achieved, not necessarily in the truths that they expound.

Unlike Plato, whose dialogues were simple mechanism to convey his ideas, the dialogues contained in the Upanishads are meant to be actual examples of how to achieve understanding by illustrating how someone has achieved understanding before.

It is by being a part of a dialogue that one comes to understand not by understanding what is said.

An example of this can be seen in a dialogue from the Upanishads between Indra and Prajāpati.

In this conversation, Indra comes to Prajāpati to understand the true nature of the self. Prajāpati keeps offering different possible selves to Indra, each of which Indra rejects until finally, Prajāpati says that what Indra has not yet rejected is the true self.

What is interesting to note is that Prajāpati takes into consideration who he is talking to.

At each point, Prajāpati offers Indra an answer he feels Indra should be able to understand, and when Indra fails to understand, Prajāpati tries again.

In addition, between each possible solution, Prajāpati tells Indra he must live longer before he will be able to understand. In other words, Indra must gain more experience on top of his excellent use of reason in order to gain understanding.

This is something not seen in Plato’s dialogues, which take place at a single time and location. Each of his dialogues could be between Socrates and anyone. The interlocutor is nothing more than a foil for Socrates.

Socrates’ interlocutors are not vital to the conversation.

Further, Socrates nor his interlocutors, ever go out to investigate what has been reasoned about so far and then return to share what they have learned.

This focus on dialogue in the Vedas and Upanishads can be seen as a result of trying to preserve many of the benefits of an oral tradition in written form.

Consider just three such benefits.

First, not everyone can read, but everyone knows a language and is able to communicate. An oral tradition makes both understanding and the process of attaining understanding accessible to all.

Second, speech is capable of conveying moods and feelings, which cannot be done in writing. A speaker’s tone, facial expressions, and gestures, all of which are used to convey feelings, are often lost in writing.

Third, what is heard is more memorable than what is seen. Hearing involves more of the sense than just hearing, such as seeing the speaker orate as well as taking in the sounds and smells of the environment one is in when listening to someone speak. thus, more of one’s senses are involved in learning.

The Early Japanese Buddhism of Kūkai

Even after oral tradition had given way to a largely written tradition among philosophers, listening still played a central part in philosophical work beyond the Vedas and Upanishads.

One such example is Kūkai, also known as Kobo Daishi (弘法大師).

Well into the 9th century, Kūkai still writes in the form of dialogues, with students and masters discussing the truths of reality.

However, it is not just his mode of presentation that makes him a good example of the listening model of philosophy.

Kūkai argues that reality itself is something to which one must listen.

Rather than reality revealing itself (a sight metaphor), according to Kūkai reality expresses itself (a listening metaphor). This brings nature itself into dialogue with people; expanding on the concept seen in the Vedas and Upanishads.

The school of Buddhism Kūkai founded is called Shingon Buddhism, whose name literally means “true words.”

Unlike the Greeks, whose ideals was an idea or image, Kūkai focuses on words.

While both are representational models, the difference is in what is doing the representing. The Greeks took it to be an image based on sight, while Kūkai takes it to be a word focusing on sound.

This is not to say that Kūkai does not think images are important or useful, only that the focus is not on images but on speech and words.

So, how does reality express itself?

Reality Expresses Itself

Kūkai describes words as physical vibrations that carry meaning that correspond to reality.

As a result, Kūkai sees words as being a totality, encompassing the physical through vibrations, the mind through meaning, and ultimate reality through correspondence.

This goes beyond the idea of the Greeks, who often argue that only one of the three is the true reality of nature.

What draws one into a more critical and rational investigation is that although reality expresses itself, one can mishear.

In order to insure what one has heard as being the truth, Kūkai claims that it must be such that what is heard represents the whole of reality.

Since we only hear a part of reality at one given time, we have to infer as to what the whole is. If we takes something to mean anything other than that which is a proper representation of the whole of reality, then we ascribe a false meaning to a word.

An example of such an investigation is Kūkai’s discussion of Om (ॐ).

He accuses other traditions such as Hinduism and other schools of Buddhism as attributing a false meaning to Om; what he calls “invariant meanings.”

Kūkai breaks down the Japanese version of the sound (阿吽 — Haūm) looking at each letter and showing how each letter’s meaning correlates to the fundamental nature of reality.

H — means the first cause of all things being unattainable.

A — means being empty and uncreated.

Ū — means existence is complete, literally “without want.”

M — means that existence is not permanent.

According to Kūkai, This is why the word haūm is chanted as a mantra in Buddhism. The word, being a combination of the letters H, A, Ū, and M, expresses complete nature of reality as it acutely represents reality’s expression of itself.

Thus, by uttering the word haūm one is able to express and be connected with the true nature of reality. It is in this true expression of reality that the true meaning of Om, and thus reality, is understood.

Conclusion

In conclusion, one can see some clear advantages that a listening model of philosophy.

First, it makes philosophy inherently communal.

The idea of Descartes locking himself in a room all by himself to see what he can discover about reality is impossible and ridiculous in a listening model of philosophy. Who would he be listening to, or who would listen to him? Listening implies the presence of at least two participants; a speaker and a listener(s).

Second, since listening involves a community, it is interactive.

Even in cases where there is a teacher, students asks questions and the teacher tailors the teaching to the students who are present. Both speakers and the listeners play off each other and take the other into account when deciding what to say and how to speak.

Third, the focus is on person to person.

A person to person focus is important in that understanding needs to be passed on from one person to another. It sees the transfer of understanding as necessary part of the process of understanding and insures that such transmission takes place.

So what do you think? Do you like the dialouges of the Vedas and Upanishads more than Plato? Is listening a better way to represent philosophy than seeing? Let me know in the comments

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed it and would like to support me, engage with this article by likeing, commenting and sharing